The egg 'cage ban' is looming, but many uncertainties remain, and no one can expect to be able to predict what will come to pass. The Ranger, the leading authority in the free range sector, explains more in this article.

Although several have tried with the inevitable degree of accuracy only a stopped clock would appreciate. We can, however, clear up some of the misunderstandings.

The UK banned battery cages for hens in 2012, but the ban did not extend to enriched cages.

So, what is the '2025 cage ban'? Firstly, it's not a ban. Well, it's not any legal regulation, at least not in Europe. Not just yet.

Nonetheless, we should remember that, as was the case following the 2012 European Directive implementation, the public at large believed that the law had outlawed cage production.

Retailer inboxes were full of consumers' dismay at the notion that all eggs were not free range, as they had interpreted the media coverage of the day.

The consumer understands the welfare benefits of free range but does not understand the complexities of different egg production systems and will be surprised to learn that colony-caged egg production continues perfectly legitimately throughout 2025 and beyond.

There was a legal impetus, however. The origins of the commitments by Tesco et al. to cease selling eggs laid by hens kept in cages are found not in the boardrooms of UK supermarkets but across the pond in Massachusetts.

Voters in 2016 passed a welfare bill to improve the living conditions for farmed animals, including outlawing cage production for laying hens from 2022.

California followed, and state by state, similar legislation has been passed. Last year, Arizona became the 10th state to make such a regulatory change.

Ahead of the 2016 votes and spotting the public relations risk of inconsistencies about to be created in federal law, large national and international food retailing and service organisations got ahead of the game with their own blanket statements.

Names such as Walmart, McDonald's, and Subway were joined by over a hundred others claiming their commitment to source and serve only eggs from cage-free birds from 2025.

Never mind that the EU had just gotten around to enforcing the end of the battery cages in use before 2012, while the UK had spent £400m on our timely compliance.

Nor that the US cage systems even today house up to a dozen moulted hens in the same barren cages we replaced over a decade ago. In the eyes of the press and probably the public, all cages were created equal.

Publicity of change involving familiar chains and brands reached our shores, NGOs dusted down their venerable 'end the cage age' petitions, and the machinations of the food industry started to stir.

By the time a student approached Tesco seeking a meeting with the management of the day (Lucy Gavaghan, remember her?), wheels were already in motion on the egg equivalent of 'me too.'

2016 marked the start of the race to replace colony eggs on UK supermarket shelves and restaurant tables with something else. But what?

The retailers' cage-free commitment is self-imposed, entirely voluntary, and open to interpretation. Referring to the eggs on sale in supermarkets, we need clarity market-wide on several variables. Barn or free range? What role will white eggs play in the value hierarchy?

Does the ban start on 1 January 2025, 31 December 2025, or another date? Does it refer only to private label (supermarket branded) cartons or branded lines as well?

Are ingredient eggs incorporated in manufactured foods or prepared meals also under the policy, or are they exempt? What caveats exist if there aren't sufficient cage-free eggs available? These are not new questions, but the answers from some chains remain elusive.

Our industry has spent much time since 2016 speculating how the order will be reconstructed to meet the changing needs of our customers.

Market commentators have gamely but vainly projected flock and system estimates for the years ahead.

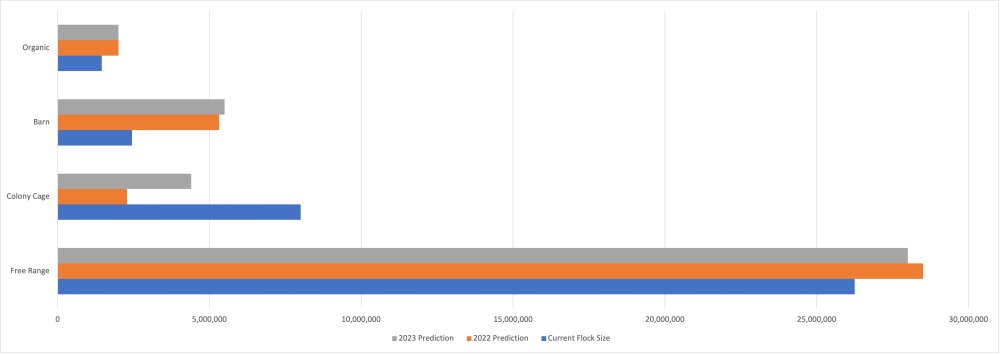

Mark Williams, then chief executive of the British Egg Industry Council (BEIC), forecast at last year's Pig and Poultry Fair that the national flock would rise to 38m comprising a smaller enriched colony flock size of 2.28m, a boosted 5.32m in barn, static 28.5m in free range and some 2m in organic systems.

Recently revised industry figures show a national population of 38 million layers. So far, so good. However, there are 8m birds still in colony cages.

Hindsight tells us that the conversion from colony to free range or barn production has been much slower than anticipated.

Retailers' lack of financial commitment to support reinvestment has been a major obstacle. It's easy to believe that this is a matter of timing! Perhaps since 2016, there didn't seem to be the right time to 'go long', from the supermarkets' perspective.

Well, not before there were insufficient eggs to go around, at least. No doubt, the doubling of wholesale prices in the past year will have slowed or even reversed the de-stocking intentions of several colony egg farmers.

At least two intensive units were decommissioned a year ago but are now back in production in response to the improved trading conditions.

The new forecasts predict that the national flock size by January 2025 will be 40 million with 4.4 million birds still in enriched colony cages, the barn flock size will double to 5.5 million, and the free range flock size will remain static at 28 million, and organic still projected at 2 million.

Compared with today's flock size, these predictions would mean the national flock will increase by 2 million birds between now and January 2025 as we approach potentially 15 months (but perhaps 27!) from the deadline.

One lesson of the last few years has been to avoid making predictions. Volatility and risk have been the extraordinary constants. To that end, it's hard to see any appetite to extend capacity across production systems.

Two million organic hens reflect a 30% increase on today's level. Cost of living pressures will curb consumption in the near future, and one can only imagine that the main reason organic sales appear supported is due to the overall lack of availability of all eggs in recent months.

Free range production is profitable again after a sustained depression. Yes, margins such as these in an ordinary world would attract investment.

But our world is currently far from ordinary; avian influenza risk, a £60/bird price tag with expensive borrowing costs, and an excruciating planning process will combine to restrict investment to either the few farmers with permissions already granted or those with broader farming enterprises that can demonstrate environmental betterment by doing less of something else.

Even at the heady £1.90/dozen being offered by some packers, you'd need bottomless pockets and nerves of steel to invest in an industry where AI insurance returns do not cover expected losses in a year while the virus shows no sign of abating.

The bed and breakfast schemes launched last year that assuage the farmer of infection risk may help keep the flock at current levels, but capacity growth feels some way off. We need the confidence of an effective vaccine for that.

Barn egg expansion makes the most sense; there is certainly a demand for it. The flock size has already doubled with early colony conversions, and with 8 million still in cages, it could double again.

But with interest rates following build costs in their mission to the relative stars, the prospect of an 8-digit investment into a large barn egg facility feels less attractive than a branch-out into space exploration itself.

This is especially so without the full financial backing of the customer who will want to drive every scrap of margin from the chain to out-compete their peers in the war for the value-orientated consumer.

Some producers are still determining if the retailers can afford to stick to their promises with eggs in ongoing short supply.

But there is no suggestion from any supermarket that this worldwide move to cage-free will waiver. We have a stand-off building, opening the way for imports and ingredient substitution.

What is more attractive to a food manufacturer or discount retailer? A UK-produced colony egg, potentially costed from a depreciated asset or a European barn egg that is in demand and priced accordingly?

As Putin's effect on the European economy unfolded, the UK supermarkets displayed stubborn naivety and contempt for the egg farmers.

Weak packers, satisfied to act as 'yes men' to the power of their buyer, must shoulder responsibility for the decimation of a fragile trust that will be harder and more costly to rebuild than it ever was to protect.

No, how the market will change, facing the combination of uncertainties, is impossible to predict, even with time running out. We're less than a full flock cycle from deadline day.

We should stop speculating on the size of our national flock and instead on how those firms committing to sell cage-free eggs from 2025 will explain their actions once the consequences of their long-term neglect of the egg industry play out.