Cattle farmers are warned to be on their guard against coccidiosis in their calves this autumn. Sub-clinical coccidiosis is often an ’invisible’ disease that can have a serious economic impact on calf production.

As an example, the infection – which destroys cells in the gut lining, can severely reduce the animal’s ability to absorb food and can cut growth rates by as much as 20 per cent. Most of the economic loss will come from calves actually showing no visible signs of the disease.

The warning comes from veterinary surgeon Nigel Underwood of Janssen Animal Health, who says autumn is a significant risk time of year for the disease. "Autumn-born calves are at great risk, particularly when housed. Cocci require warmth and moisture to survive, and cattle housing is ideal for them."

This warning also extends to cattle born earlier in the year. "They may not have been exposed to the disease, which means they will not have built natural immunity and will also be at risk." Data collected by the National Animal Disease Information Service (NADIS) and the Veterinary Investigation Disease Analysis (VIDA) show coccidiosis outbreaks are significant in the autumn housing period.

Coccidiosis is well known as one of the most common causes of diarrhoea in calves. "But it is frequently overlooked because of the difficulties of diagnosis when diarrhoea is not present, and there has also been a lack of awareness of the consequences of this disease on production," says Nigel Underwood.

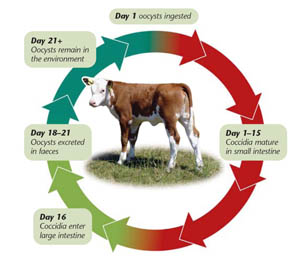

Coccidiosis is caused by calves picking up oocysts (eggs) of a single-cell parasite, Eimeria, shed onto pasture in the dung of previously infected animals. One ingested oocyst can multiply to 16 million shed in the 17-22 days the parasite is in the animal. These become infective in two to seven days.

A calf can pick up from 5,000 to 10,000 oocysts a day from pasture or bedding. The infective oocysts ’hatch’ to produce the stage of the organism which penetrates the intestinal cells. They destroy millions of cells in the gut lining, severely reducing the animal’s ability to use feed and to grow to its genetic potential.

Signs of the disease do not appear until the parasite’s life cycle is almost complete, which is when it is causing most damage. Clinically diseased calves show a number of symptoms – anorexia, weakness, fever, diarrhoea, anaemia, tenesmus and signs of abdominal pain.

A strategic application of a single dose of the anticoccidial oral drench Vecoxan™, on farms where coccidiosis is known to be a problem, has been shown to improve average daily gain by 20 per cent-plus. It also reduces oocyst production by 98 per cent, dramatically cutting the contamination of pasture and bedding. "This is important – oocysts can remain infective for up to two years," he adds.

Vecoxan has been licensed for use in cattle since 2006. It has a well-proven record in treating and preventing coccidiosis in lambs – contributing significantly to the UK sheep industry’s financial returns for many years. A POM-VPS medicine, with the active ingredient diclazuril, it is available from veterinary surgeons and authorised merchants.

To obtain maximum benefit, all calves in a group should be treated simultaneously about two weeks after they have been exposed to a significant oocyst challenge. This is known as metaphylactic treatment, which enables calves exposed to coccidiosis to develop natural immunity without any visible clinical symptoms of the disease. Vecoxan does not interfere with natural immunity development.

Calves with clinical disease are likely to need further supportive treatment to overcome the effects of dehydration and secondary bacterial infection.

The drench is given at a rate of 1ml per 2.5 kg bodyweight. It is safe to treat beef and dairy calves, indoor or out, and there are no restrictions on the weight of calf that can be treated.

There are no environmental issues with Vecoxan. The manure from treated animals poses no threat to plant life and it can easily be spread onto the land without the need for special management. The product has a zero day withdrawal period for meat and offal.

"The animal welfare and financial consequences of the disease can be dire," says Nigel Underwood. "Assessing the autumn challenge and instituting a preventive treatment programme, particularly covering autumn-born calves, will have significant benefits for animals and farmers."