Compared to 2008 agflation is sustained and kinder to developing economies but the threat of government intervention looms

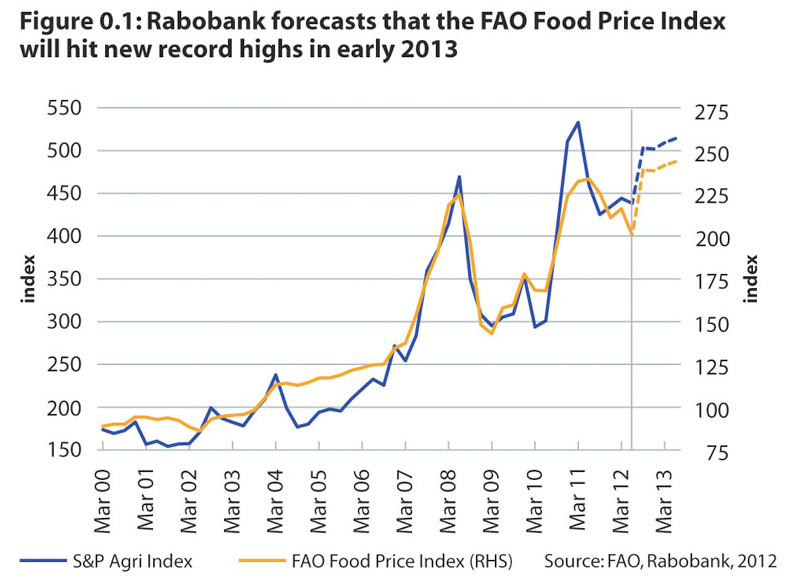

Skyrocketing agricultural commodity prices are causing the world to re-enter a period of "agflation", with food prices forecast to reach record highs in 2013 and to continue to rise well into Q3 2013.

Unlike the staple grain shortage of 2008, this year's scarcity will affect feed intensive crops with serious repercussions for the animal protein and dairy industries.

“The impact on the poorest consumers should be reduced this time around, as purchasers are able to switch consumption from animal protein back towards staple grains like rice and wheat" said Luke Chandler, Global Head of Agri Commodity Markets Research at Rabobank.

"These commodities are currently 30% cheaper than their 2008 peaks. Nonetheless, price rises are likely to stall the long-term trend towards higher protein diets in Asia, the Middle East and North Africa. In developed economies – especially the US and Europe – where meat and corn price elasticity is low, the knock-on effect of high grain prices will be felt for some time to come.”

Due to the long production cycles of the animal protein and dairy industries, the affects of grains shortages will be more sustained as herds (especially cattle) take longer to rebuild, maintaining upward pressure on food prices. However, food makes up a smaller proportion of budget spend in such countries, so the current period of agflation should not lead to the unrest witnessed in response to the shortage in 2008.

Rabobank estimates that the Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) Food Price Index will rise by 15% by the end of June 2013. In order for demand rationing to take place, in turn encouraging a supply response, prices will need to stay high. As such Rabobank expects prices – particularly for grains and oilseeds – to remain at elevated levels for at least the next 12 months.

Government intervention

Whilst the impact of higher food prices should be reduced by favorable macroeconomic fundamentals (low growth, lower oil prices, weak consumer confidence and a depreciated US dollar); interventionist government policies could exacerbate the issue. Stockpiling and export bans are a distinct possibility in 2012/13 as governments seek to protect domestic consumers from increasing food prices.

Increased government intervention will likely encourage further increases in world commodity and food prices.

Rabobank expects that localised efforts to increase stockpiles will prove counterproductive at the global level, with those countries least able to pay higher prices likely to see greater moves in domestic food price inflation.

This is a vicious circle, with governments committing to domestic stockpiling and other interventionist measures earlier than usual—recognising the risk of being left out as exportable stocks decline further.

On top of that, there are warnings that global food stocks have not been replenished since 2008, leaving the market without any buffer to adverse growing conditions. Efforts by governments to rebuild stocks are likely to add to food prices and take supplies off the market at a time when they are most needed.