Spectral imaging 'key' to monitoring crops more effectively

Spectral imaging holds the key to monitoring crops more effectively, according to agri-tech start-up Fotenix.

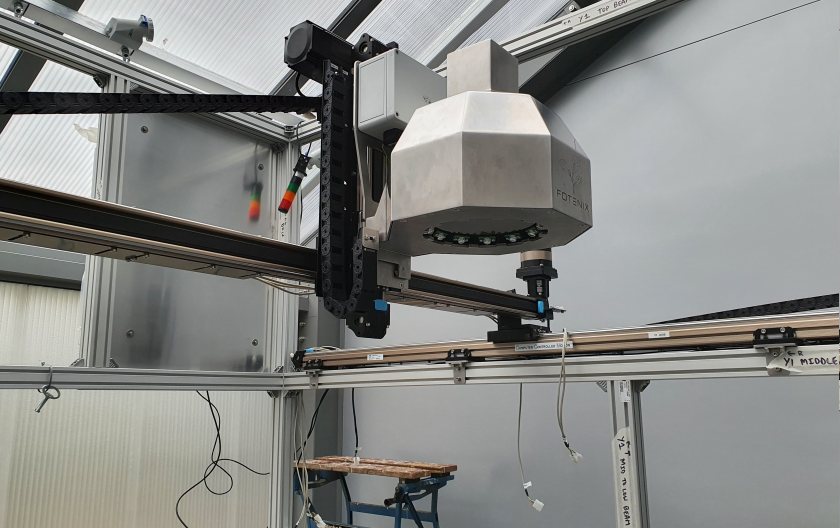

Fotenix have combined the use of cameras that deploy different colours of light with machine learning to better monitor crop health.

The technology is able to identify diseases in real-time before they develop symptoms that are visual to the human eye.

The company say that this means laboratory level analysis can be used in field situations at an affordable cost.

Dr Charles Veys is an expert in agri-tech engineering who set up Fotenix in 2018 after working as a research engineer at the University of Manchester.

He said: “I had been working on mounted cameras which can identify the presence of different plants.

"I soon realised that we could take this much further by using diagnostic technology, such as spectral imaging, in the field environment.”

Integrated technology

Fotenix have an unusual business model in that they are not a direct service provider to the farmer, instead they operate by enabling businesses that are already providing technology.

Dr Veys likened it to the Apple Car Play system that comes inbuilt with the car: “We think it is an inefficient system to go around retrofitting our technology onto people’s equipment.

“Instead, we think it makes sense to deal directly with machinery or service providers and embed our technology within their equipment.

"For a retrofit model to work, we would have to work directly work with the manufacturer to ensure reliable integration on farm.

“For example, a farmer who is already using a farm management platform will have the data our technology provides come through to them on that existing platform and they might never know we exist.”

This means that the technology can be rolled out across a wide range of different applications and agricultural sectors.

“Although we are working on a lot of different projects, the hardware that actually goes into the systems does not vary that much,” Dr Veys explained.

“Typically, what changes are the problems we are facing, for example the issues we are looking to tackle in a field of wheat are very different to those we are dealing with in a glasshouse full of tomatoes.”

The science

Dr Veys offered an insight into how the technology actually works: “What we do is use our own LED light and record how that light reflects, which gives us a digital twin of the plant and the information inside the leaf.”

This is because Fotenix use different coloured lights - which are at different wavelengths - that can penetrate different parts of the leaf.

“For example, infra-red tells us a lot about the inside of a plant, which is really useful for diseases in their early stages when they are not showing any symptoms on the surface, whilst colours like green pick up a lot of information on the surface of the leaf," he said.

They then use this information to create a library of different models which can be used for different applications, crops, and diseases.

The technology is aimed particularly at diseases before they show visible symptoms, with considerable focus on Septoria in wheat and Light Leaf Spot in oilseed rape.

Dr Veys explained: “Once a disease is visible then the plant is already stressed, and it is too late.

"We are trying to target diseases which you would typically have to find by sending off samples to a laboratory.”

In practice

The aim of the technology is not to make decisions for farmers, but instead Dr Veys insists it is to give farmers and agronomists the best possible intelligence to make their decisions.

“We are informing the way people can target their resources, in the same way as a doctor might look at an x-ray to help inform their medical decisions,” he added.

Fotenix envisage the technology being used in lots of different forms. In the arable sector they say it could be used on equipment like a fertiliser spreader as it travels through the crops, recording data and informing fungicide applications.

“In the nearer term we are bringing out a handheld system this summer which will go into the hands of agronomists, giving them the ability to look beyond their visible range,” Dr Veys said.

He also said that they are working with robotics companies who are looking to develop robots to autonomously sample plants, particularly at night when the technology is most effective.

“We are at different stages in different markets. We are on our second commercial deployment on polytunnels and glasshouses, whilst we have more work to do in the arable sector.

"It is natural that the technology is going to be used on higher value crops first”.

For this reason, the technology is most advanced in the breeding market where it is has been used for some time.

Breeders are able to get a clearer picture of which varieties are more resistant to diseases and therefore make decisions between them.

Looking forward

Dr Veys believes that the affordability of the technology means it has a strong future: “Tight margins in agriculture mean that we need to be making sure that our intelligence fits alongside the machinery farmers are already using.

“The nice thing is that we are using cameras that are essentially the same as those in a mobile phone, so we are making sure that this remains affordable for farmers.

"I think this has the potential to become fairly commonplace, in the same way as sat nav is now used in travel.”

He believes that the growth of agri-tech is about to pick up pace: “I think the combination of Brexit and the pandemic has focused a few minds and made people really think about what paths need to be automated.

“We cannot expect farmers to be more sustainable and produce food at a cheaper price if there is not the facilities or infrastructure there to do that.”