Nature’s original purpose for the egg was as a protective development chamber for an embryo which could grow into a day old chick. With the modern free range layer, the aim is to produce eggs specifically for human consumption.

Today’s successful free range layer flock will be one where the hens lay plenty of eggs capable of meeting stringent market requirements.

Success is based on producing the highest percentage of saleable first quality eggs of the right size!

Egg production can be likened to a car assembly line with different components of the egg added at different stages as the egg makes its journey from ovary to outside world. As in car production, things do not always run smoothly.

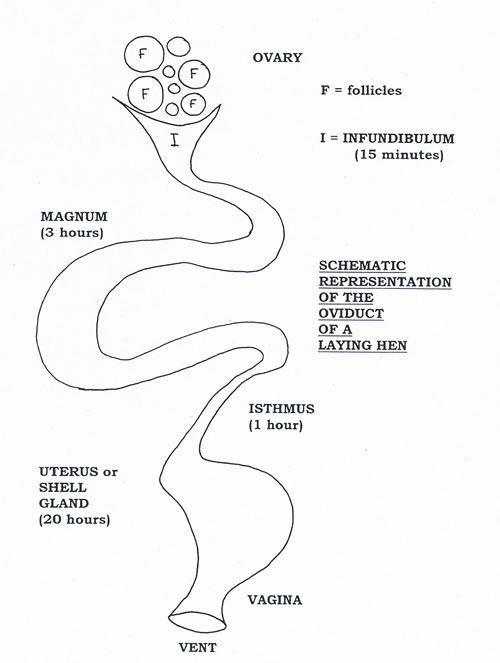

The key areas involved in the " egg production line" are:

The ovary:

The life of the egg starts in the ovary. The hen’s ovary looks like a big bunch of yellow grapes and is, in fact, a collection of yolk packages (follicles) of varying ages. About one per day is "ripe" enough to detach itself and drop into the infundibulum. This procedure is under hormonal influence to control the rate of maturity of the ovarian follicles and the hormonal mechanism is influenced primarily by the lighting programme to which the birds are exposed. This explains why lighting programmes are so important in triggering a flock, as a whole, to "come into lay".

The ovary has a very rich blood supply and can act as a "filter". If birds are suffering from a bacterial infection and there are bacteria in the bloodstream, they may settle in the ovary hence bacteria such as Salmonella enteritidis can be incorporated into the ovary and find their way into the egg.

The colour of the yolk is determined largely by the diet of the bird. Natural pigments in the feed are absorbed from the gut and are transported to the liver and then to the ovary. If there is any damage to the intestine, such as can occur with severe worm infestation or bacterial infection, then there may be poor absorption of pigments from the gut and hence poor yolk colour.

The oviduct:

The second major organ in the chain of egg development is the oviduct. This is the production line although it is a long flexible tube rather than a conveyor belt.

The infundibulum:

The top end of the oviduct tube is a funnel-like structure called the infundibulum which catches the maturing follicle as it drops off the ovary. This sounds easy but it is at this stage that things can start to go wrong. When a flock first comes into lay (and under certain dietary influences), more than one follicle can develop rapidly and drop into the infundibulum at the same time. These then go on to be double yolked eggs.

The magnum:

This is the longest and most obvious part of the oviduct. One major problem here is that as the oviduct is a long tube of circular muscle, it squeezes the egg along like toothpaste in a tube or like food moving along your intestine. In the same way that you may suffer nervous diarrhoea under stressful circumstances due to unwelcome contractions of these muscles, any stress on the birds can upset the rate and direction of movement of the egg on its travels.

The infundibulum may even contract and prevent the ripe follicle gaining access to the magnum at all. If this happens, the mature follicle has to go somewhere and will drop off into the abdomen. Once in the abdomen, it is likely to burst, irritate the delicate lining of the abdomen and lead to a sterile egg peritonitis. For this reason, it is not uncommon to see a blip in mortality at the onset of lay, especially if the flock is under stress.

The magnum is lined with special glands and this is where the albumen (white) is coated onto the egg follicle (yolk). General stress and certain viral infections can disturb the function of these glands and result in very watery albumen being produced. This can lead to the all too well known problem of "watery whites" reducing the Haugh units and increasing seconds.

The magnum is a very blood rich organ and "stresses" can cause aberrant muscle activity leading to some small haemorrhages (bleeds) resulting in so called "blood spots" in the albumen. Sometimes small pieces of tissue may become detached from the lining of the magnum and can result in "meat spots" in the finished egg.

The isthmus:

The next section of the oviduct through which the egg passes is the isthmus. This is a narrow section and here the egg membranes start to be laid down around the albumen to package it correctly. These egg membranes are very important. They act like the foundations of the house and if they are not laid down uniformly and accurately, the shell itself may be a disaster!

The uterus (or shell gland):

The first section is a short tube called the tubular shell gland. Here calcium salts are deposited on the egg membranes to produce the first layer of bricks on top of the foundations. If this layer is built incorrectly, then the shell laid on top may be crooked, weakened, deformed, roughened, abnormally pigmented or prone to cracks. The egg may only spend a short time in this part of the oviduct but it is critical to good shell development and hence production of first quality eggs.

The second part is the true shell gland or pouch. The egg spends most of its time here (about 20 hours) and during this time there is a considerable increase in the weight of the egg due to fluid and shell deposits. 95% of the egg shell is made up of calcium carbonate, so good shell development is dependent on a good source of calcium for the bird, delivered via the feed in a way the bird can effectively absorb it.

During this phase, lack of adequate perching space can lead to crowding of birds causing abnormal pressures on the birds abdomen and hence on the unlaid egg. This can lead to misshapen eggs and cracks (especially equatorial) and other deformities.

The vagina:

The egg has now virtually finished its journey to the outside world and the vagina represents the "waiting room" prior to the selection by the bird of a suitable nest site for laying. This last stage, like childbirth for women, may be the most dangerous part of the process. The hen is at her most vulnerable just after she has laid her egg and if not left to perform this task in peace and quiet, she may leave the nest prematurely and her red, glistening vent may be too much of an invitation to her sisters. Pecking damage can result leading to trauma and distress.

In addition, as the description of this journey has explained, the oviduct represents an opening from the vent right up into the abdomen of the bird. Any infection introduced at the vent can find its way deep into the bird and lead to the condition of egg peritonitis.

Incidentally, on the rare occasion that roundworms are found in intact eggs, they have travelled this same route up the oviduct and into the albumen before the shell and its membranes have formed.

CONCLUSIONS:

As you will see from the above, the egg has a complicated and arduous journey from ovary to outside world. All sorts of things can go wrong with the process and it is probably something of a miracle that things go smoothly most of the time!

As described above, while the normal flow of egg production is down the oviduct, sometimes parts of the egg or even virtually finished eggs can move back up the oviduct by a process of reverse peristalsis. In extreme cases, this may result in a soft or partly shelled egg moving right back up the oviduct and dropping out of the open end into the abdomen so if the bird were to be opened up, one would find shelled eggs in the abdomen (this condition is known as an internal layer). In less extreme cases, the egg may move a short way up the oviduct and come back down again and it is possible that a second layer of shell can be deposited on an already partly completed egg. These aberrations in the production process happen quite frequently and the trigger factors are not fully understood, but can produce some bizarre looking individual eggs!

As with any production line, best results are obtained when the worker is kept happy. This is best achieved by producing consistent and mature point of lay pullets in the best possible condition and following up with good food and lots of TLC in lay. Contented hens lay good eggs!

Claire Knott, Stephen Lister, Philip Hammond & Ian Lowery

Crowshall Veterinary Services