The British Free Range Egg Producers Association will mark the 20th anniversary of its formation this year.

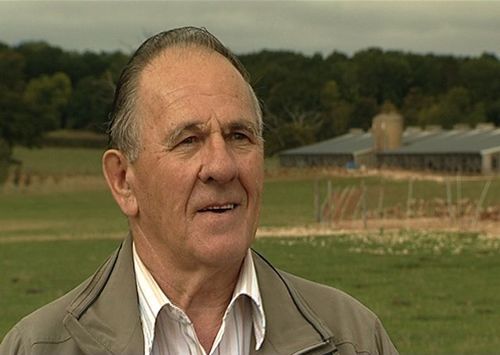

It was in December 1991 that a group of free range egg producers gathered in the London offices of the National Farmers Union to establish the fledgling organisation. At the time free range accounted for only a tiny fraction of UK egg production; today 45 per cent of all eggs passing through the country’s packing stations are free range. Yet despite the vital role that free range now plays in the UK egg industry, founding chairman Christopher Bannister says that it still faces the same problems it faced when the association was formed two decades ago.

"The situation then was exactly the same as the one the industry is faced with now. Absolutely terrible prices; screwed by the packers and high feed costs," he told the Ranger. He said a small group of producers in Sussex felt the answer would be to form an association to represent free range interests. They advertised the London meeting, just over 100 producers attended and BFREPA was formed.

Since its inception, BFREPA has done a great deal of good for free range producers. It managed to prevent some of the worst excesses that could well have been written into welfare rules, it has spoken up for free range within the egg industry and at Government level and it has provided a forum for producers to share their problems and their successes. It has even, to some extent, been able to press for better returns for free range producers, although the association has been powerless to avert the current financial crisis that has resulted from uncontrolled expansion of the free range sector. Today’s chairman, John Retson, believes that BFREPA must do even better as an organisation if it is to prevent a similar crisis happening again.

"BFREPA can be proud of its 20-year history. It has had many successes over the years, but we have never had to face market conditions like this before," said John, who said he wanted to see the association grow its membership and also pursue a far more professional approach. He has said he would like BFREPA to represent 80 per cent of UK free range egg producers so that it could speak for the sector from a much greater position of strength. He and the council are also pursuing other initiatives.

A new director of policy is being appointed to deal with the day-to-day running of the organisation. John also wants BFREPA to develop its own statistical analysis of the egg market to enable the association to foresee potential oversupply and act to prevent producers suffering the severe financial hardship they are currently experiencing.

Although Christopher Bannister retired from egg production two years ago, he says he can still see at close hand how producers are struggling in the current financial climate. He let his free range egg units to a young couple who, he says, are experiencing the same terrible financial difficulties that other free range egg producers are having at the moment. "To see them struggling as they are is heartbreaking. We are not charging them any rent – we have not done so for the last six months. They are putting so much effort in but they are losing money hand over fist."

He says his biggest regret was the association’s failure to grasp the co-operative nettle in 1994. The association raised £15,000 from producers, which was matched by £15,000 in Government grant, for a feasibility study into establishing a co-operative. The study was carried out and Christopher said the advice from it was not to seek confrontation with the packers by setting up packing stations, but to form regional producer co-operatives to control production and negotiate prices with the established packers.

"We held an open meeting. The packers sent their representatives there and made it clear that if it was voted to go ahead the people in that room who voted ’Aye’ would lose their contracts. Nobody had the courage to stand up and that opportunity was lost, I believe, forever. It will never happen now," he said.

"What we wanted was to have some kind of input into the selling price of our product. Other manufacturers don’t ask the person they are selling to what they are prepared to pay. They give them a price." He said co-operatives would have been able to control production and would have only taken on extra production if there had been a need for it. "At least we would have had some control when we got to situations like we have now. We would have seen chick placements three years ago, we would have seen what supply and demand was, we would have had intelligent people, who would have been working the industry for 10 or 15 years, knowing what was happening."

Christopher Bannister believes co-operatives could have made a big difference to the fortunes of free range egg producers today – just as the producers who met to form the association in London felt that BFREPA could help stand up for producers who first started to feel the effects of price pressure in 1991.

"When things are going along happily you don’t really feel you need an organisation," said John Widdowson, a founding member of BFREPA and long time editor of Ranger. "It is only when the pressure is on and the pressure was coming from two fronts at that time. The first was that 1991 saw the first decline in free range egg prices when there had been boom times until then. That was the first time we saw some market pressure; big drops in prices. There was also political pressure. I remember quite clearly that the Farm Animal Welfare Council (FAWC) was looking at free range. Up until then (and it was a very small industry at the time) producers had been able to go on without any political interference. Suddenly all these things that we are now so used to – other bodies looking at us and setting standards – were raising their heads for the first time."

John was amongst the small number of producers who formed the first BFREPA council, which met for the first time in January 1992. Along with chairman Christopher Bannister, the officers included vice chairman Peter Barton, treasurer David Smith and secretary Jean Bannister. John Widdowson represented the South West region along with Graham Frankpitt, Dave Rusbridge and John Jochimsen represented the South East, Jeff Vergerson and E.J. Perone represented East Anglia, and David Trick and D.C. Moore were the Central region representatives. From the West Midlands there were Richard Kempsey and Tony Wilmott, from the East Midlands Des Bradley, from the North East Malcolm Mackinder and Peter L. Hudon and from Wales Gwynfor Hughes and Chris Brown.

In a letter to council members prior to that first meeting, Christopher Bannister said, "We have been given a great opportunity to grasp and have some influence over our future. The problems facing us will not be dealt with easily. Some, indeed, will bring about, I am sure, heated discussion within the committee, but unless we arrive at a consensus of opinion over welfare standards in particular, we will have no influence in the areas that matter and will have standards imposed that none of us will agree with and we will deserve it. I urge all of you, therefore, to meet with an open mind, with a real willingness and positive desire to arrive at a conclusion." He said, "We have much to achieve and a great deal of effort to expend in arriving there."

Welfare rules were clearly a concern at the time, and David Trick, who took on the chairmanship of the association in 1994, said that BFREPA had some notable success in this area – particularly with the RSPCA. Representatives spent a great deal of time dealing with the RSPCA, in particular, and preventing the introduction of far more draconian requirements, he said. "They had very strong views on egg production. They certainly would not approve any intensive production. We had quite a lot of up and downers in our involvement with them," said David. "We tried to keep a balance between RSPCA views and our members."

David said that the Freedom Food standard was born during his chairmanship of the association and BFREPA was very active in influencing the way that the code was drawn up. "The majority of the influential people in the RSPCA wouldn’t like the way that farm animals and birds are kept. All the way along the line we had to keep putting our points of view and arguments and for several years I think we were fairly successful in influencing some of the organisation who, I think, would have preferred to go in a different direction."

David said that birth of Freedom Food presented challenges in its own right. "You have the producer on the one hand who feels the regulations are too tight and on the other you have the RSPCA, who think they aren’t tight enough. It’s a case of trying to keep a reasonable balance on these things."

David’s tenure was a period in which free range egg production began to expand, and with that expansion came wider recognition. In 1996 BFREPA was invited to join the British Egg Industry Council. As well as representing free range egg producers’ views to welfare organisations like the RSPCA, it established contacts with the Ministry of Agriculture and also began to meet supermarket representatives – a clear indication of the emerging importance of free range in the egg sector. Current vice chairman Jeff Vergerson said that supermarkets responded to increasing interest amongst consumers. The packers, in turn, had to respond to the demands of the supermarkets. "Not many packers were particularly interested in the early days," said Jeff, who recalled one packer he approached turning him away only to subsequently call him back after the packer was contacted by one of the major retailers.

Tom Vesey, BFREPA’s longest serving chairman, from 2000 to 2009, said that, even after the association was invited to join BEIC, free range was not really taken seriously at first. "I remember three of us went along to a meeting. We said we wanted more money and they looked at us as if we were completely mad. Then they said good morning and we walked back out again."

Tom said that the view of free range only began to change when growth really began to take off towards the end of the 1990s. He said that from about 1999 free range began to grow at eight, 10, 12 per cent each year. "They were forever chasing increased numbers. Everybody else went down and we went up for about 10 years," he said. "The BEIC took us seriously and the supermarkets decided we were worthwhile talking to."

Of course, the fact that free range has become mainstream has meant that in many people’s eyes free range eggs are now a commodity. Tom said that the more profitable times for free range egg producers were when free range was still a niche product. "It was still a bit special then and producers could practically charge what they liked. As soon as we became a commodity things became tighter," said Tom. "It has always been cyclical. We used to be in the blackest of despair thinking that growth had been overtaken by the numbers, but within six months the growth had caught it up and away we went again. No-one makes a fortune in agriculture but it was a very good living that everybody made," he said. "We certainly had nothing like producers are suffering now."

Tom said that, as free range expanded, the industry inevitably had to change. Hand collection was replaced by automation and flock sizes increased to meet the growing demand for free range eggs. He said that one of the biggest battles during his time in office was persuading Freedom Food to agree to an increase in external stocking density on free range units. "There were always welfare issues during my time to try to make sure that Lion and Freedom Food to practical levels, but I think the biggest battle – and it took a long time – was getting Freedom Food to agree to change the external stocking density, which then allowed the smaller producer, in particular, to increase the size of his unit." With the oversupply problems now facing the industry, Tom says he is not sure whether it was the right thing to do. "Only time will tell," he said.

The battles over prices and welfare rules were probably the issues that caught the eye, but Tom believes that amongst the greatest benefits provided by the association was the simple ability to share worries and experiences. "Farmers tend to beaver away on their own, and BFREPA provides a tremendous talking shop. People can see that they are not alone; that others are having the same problems as they are."

Through the association, free range egg producers were able to share ideas and solutions, offer their thoughts on new technologies and learn from the experience of others. The Ranger provided a medium for members to raise issues and voice concerns. Under the editorship of John Widdowson, aided by former journalist Peter Whitehouse, it grew from being a single sheet newsletter into a respected magazine. Today, under the direction of Keith Wild, it is the leading magazine in the egg industry.

And then every year members turn out in great numbers for the annual conference. They elect their leaders, vote in the annual awards, discuss all the issues of the day and get up-to-date with all the latest offerings from the huge number of trade exhibitors who recognise the significance of the association and its importance to the free range sector.

This year they will gather for the conference on November 17 at Stoneleigh Park. The fact that it will take place shortly before the association’s 20th anniversary will, no doubt, add a little significance to this year’s event.