The history of agriculture is the story of humankind's development and cultivation of processes for producing food, feed, fiber, fuel, and other goods by the systematic raising of plants and animals.

Historian journalist Deborah Barham Smith gives FarmingUK an exclusive in-depth journey into the history of humankind's greatest invention.

Click here to read Part One of the story of agriculture.

We are so used to seeing fields of cows, most commonly the Holstein-Friesian breed - which represents 90% of the British herd; and the black and white one that most school children would draw.

Other breeds can include the Ayrshire, Jersey and Guernsey, but does it occur to many of us to wonder how the humble cow evolved?

In the first part of a history of farming, we saw the development of land preparation and crop growing, from the Fertile Crescent through to the advent of mechanisation.

Now is time to explore cattle in greater depth, since without some of their ancestors, ploughing and land preparation might still be in the Dark Ages.

About half the world's crop production is thought to still depend on animal traction for land preparation, such as ploughing.

The importance of cattle - such as oxen

Whilst the horse clearly played a large part in the development of farming, ploughing, pulling wagons and tree felling, pack horse trains distributing goods, etc, little is mentioned about the significant role contributed by cattle such as oxen.

It appears that as few as 80 cattle (first domesticated in southeast Turkey about 10,500 years ago) were the predecessors from which all our modern herds evolved.

Some societies consider cattle the oldest form of wealth, and cattle raiding consequently was one of the earliest forms of theft.

In remote areas of the UK, rustling can still be a considerable and costly issue for farmers; some are even, in desperation, resorting to dyeing their sheep in garish colors such as orange to protect them.

In years gone by, owners of stock had predators to worry about that no longer are an issue in most parts of the UK – the wolf was a serious threat to livestock and human life, but was exterminated from Britain through a combination of deforestation, active hunting and bounty systems.

In 950 several criminals, rather than being put to death, were ordered to provide a certain number of wolf tongues annually.

The Norman Kings employed servants as wolf hunters, and many held lands granted on condition that they fulfilled this duty.

The Anglo Saxon Chronicle states that January was known as Wolf manoth, as the first full month of wolf hunting by the nobility.

Officially, this hunting season would end on March 25; to encompass the cubbing season, when wolves were at their most vulnerable, and their fur of greater quality.

Wolves were so numerous in Northumbria, that it was virtually impossible for even the richest flock-masters to protect their sheep, despite employing many men for the job.

In 1577, wolves caused such damage to the cattle herds of Sutherland that James VII made it compulsory to hunt wolves three times a year, while bounties were still maintained in the East Riding until the early 19th century.

One family called Wolfhunt, lived in Peak Forest in the 13th century; their occupation as their name suggests was to clear the wolves from the area.

It was reported that the last wolf killed in England was at Wormhill Hall (Derbyshire) in the 15th century, (a fact disputed by other places).

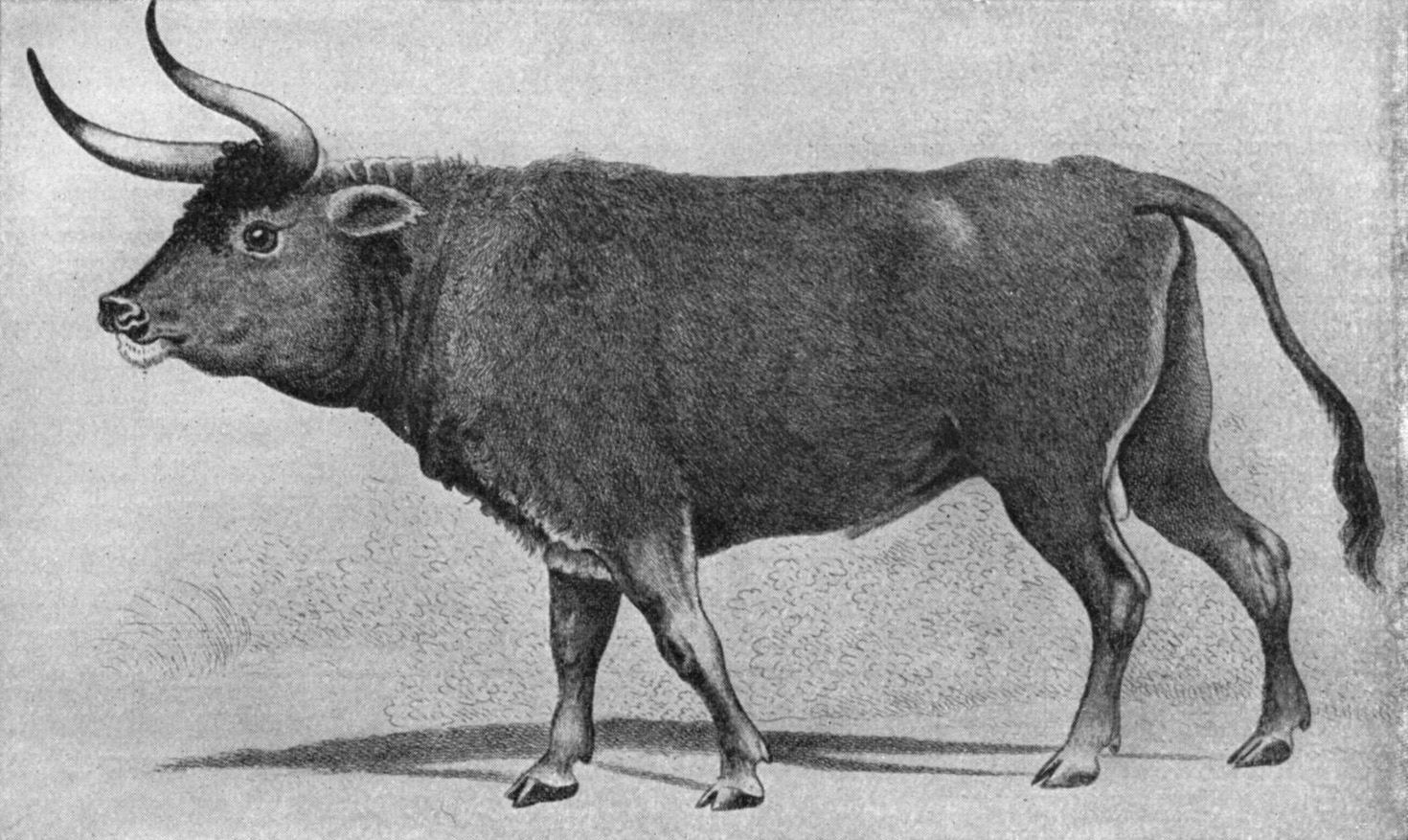

Another close ancestor to modern breeds was the Auroch - a species of wild bull, that originally ranged throughout the forests of Europe, North Africa and much of Asia; they were hunted to extinction in the 17th century.

Historically becoming restricted to Europe, the last known individual died in Poland, in about 1627.

Nazi-engineered cows for Hitler's Germany

Hitler’s obsessive drive to produce the perfect Aryan race was not merely confined to people – it also extended to this specially bred herd of Nazi-engineered cows.

Zoologist brothers Heinz and Lutz Heck (in Munich and Berlin respectively) were commissioned by the Nazi party to produce a breed of cattle based on aurochs (the Aryan Cow).

They attempted to recreate cattle of similar appearance by crossing traditional types of domestic cattle, creating the Heck cattle.

Lutz in Berlin used Spanish fighting bulls, whereas Heinz experimented with a mixture of Hungarian Greys, Highland, Corsican, Murnau-Werdenfels, Angeln, Black-pied lowland, White Park, and Brown Swiss cattle.

The Berlin breed did not survive WWII, so all modern Heck cattle derive from the Munich experiments.

In 2015 Derek Gow, a farmer in West Devon imported more than a dozen of the Heck super-cows in 2009 (nearly a century after they had been engineered)but was forced to slaughter seven of the herd since they were so extremely aggressive.

They repeatedly tried to kill his staff, so they ended up in what he described as ‘very tasty sausages tasting a bit like venison’.

The Heck cows, bred from wild genes extracted from domesticated descendants of the aurochs, had such muscular physiques and deadly horns that they were used in propaganda material during WWII as a further illustration of the Third Reich’s strength.

"There was a thinking around at the time that you could selectively breed animals for Aryan characteristics, which were rooted in runes, folklore and legend.

"What the Germans did with their breeding programme was create something truly primeval," said Mr Gow.

"The reason the Nazis were so supportive of the project is they wanted them to be fierce and aggressive.

"When the Germans were selecting them to create this animal they used Spanish fighting cattle to give them the shape and ferocity they wanted."

Bull-baiting in early England

One horrendous thing that happened in early England was bull-baiting, not only practised as a form of recreation, but because of many towns’ by-laws.

These regulated the sale of meat, and stipulated that bulls' flesh should be baited before any were slaughtered and put on sale.

It was believed that baiting improved the flesh!

These laws continued through the eighteenth century, but by the early nineteenth century were starting to die out, mainly because the baiting caused a public nuisance and not because of new ideas about animal cruelty.

The RSPCA would have had a field day!

A Bill to suppress the practice was introduced to the House of Commons in 1802 but was (perhaps indicative of those times) defeated by 13 votes.

It was only finally outlawed when the Cruelty to Animals Act was passed in 1835.

Still coming under the umbrella term of cattle, oxen are often given little recognition for what they contributed in the past in the UK - an ox (known as a bullock in Australia and India) is a large bovine trained as a draft animal.

Oxen are commonly castrated adult male cattle, making them far easier to control; they could well be nicknamed the Living Tractor for their strength.

Oxen are thought to have first been harnessed, yoked and put to work around 4000 BC.

They are able to pull heavier loads, and for a longer period of time than horses depending on weather conditions.

When hauling freight, oxen could move very heavy loads slowly and steadily, but are at a disadvantage compared with horses when needed to pull a plough or load of freight quickly, unable to cover as much ground in a given period of time.

For agricultural purposes, oxen were more suitable for the heavy tasks such as breaking sod or ploughing in wet, heavy, or clay-filled soil.

For millennia, oxen also could pull more substantial loads because of the use of the yoke.

Yoke - a wooden beam used between a pair of oxen

A yoke is a wooden beam normally used between a pair of oxen or other animals to enable them to pull together on a load when working in pairs, as oxen usually do.

There are several types of yoke, used in different cultures, and for different types of oxen.

A pair of oxen may be called a yoke of oxen, and yoke is also a verb, as in "to yoke a pair of oxen".

Until the invention of the horse collar which allowed a horse to engage the pushing power of its hindquarters in moving a load, horses could not pull with their full strength because the yoke used on oxen was incompatible with their anatomy.

For 2000 years or more, oxen were the main beasts of burden on roads and farms in Britain.

Two oxen yoked together and carefully matched for size, strength and height could compete with any single horse and had the advantage of being more robust and less likely to be injured.

Plus they could exist on poor food such as dodgy straw and mouldy hay that no horse would eat, and at the end of their lives, still made good beef!

Oxen had to be shod which was not the easiest job since they have cloven hooves, which involved fitting two half-moon shaped iron shoes or cues to each foot, and securing them with flat headed nails.

Oxen could not lift each foot to be shod – if this was tried, they fell over.

So the oxen must be lifted entirely off the ground with a hoist and straps to be shod.

When they needed their hooves worked on, a tipping table was the only thing that would work & even then one had to restrain their legs & head.

An oxen frame had a crank-up hoist for picking the animal off the ground.

If a frame was not available, the animal would be thrown with ropes, then its legs tied to a wooden stave so it couldn’t move; then a lad had the job of sitting on its head - like a horse - if it cannot raise its head, it won‘t be getting up!

In Cornwall, oxen were still ploughing at Bodrugan in Cornwall, and also in the same county at the manor of Tregear, but mostly were not used after 1850.

The latter belonged to the Bishop of Exeter and was important enough to have its own resident blacksmith to shoe the oxen – a pair of ancient ox shoes was discovered there, as near Buxton recently.

In Western Europe, records dating from before the Norman Conquest mentioned oxen being shod by rural farmers.

The demise of the oxen

They all but vanished in the years between 1800 and 1840 due to social reforms, industrialisation and the need for more speed.

The Enclosures Act of 1801 was greatly instrumental in their demise, since a large team of oxen harnessed together in pairs could not negotiate the smaller fields whereas the horses could do. Enclosure also robbed the common man – pushing him off the land and into towns.

But then before much longer came the steam traction engine with far superior ‘horse power’, and the world of farming was transformed for ever. Mechanisation had arrived.

How times have changed...

How times have changed - many farmers have had to diversify to stay in the business of farming, which is now, of necessity, profit driven.

Milking facilities used to be in shippens in the not too distant past with cows tied individually and handled by the cowman, some even had names like Buttercup and Bluebell; now numbers have taken the emotion out of the whole process and added to the paperwork.

Now it can be fully automated mobile parlours out in the field, which are moved to be in the right place for the cows who take themselves in to the milking stalls themselves when they feel the need to be milked and everything happens like clockwork with computerised records.

It used to be a collection of country folk working a farm.

I remember as a child on summer holidays, helping to stacking sheaves to dry and irritating my uncle when we made houses out of them, travelling home on the top of the trailers piled high with straw bales and feeling so important, with no thoughts of Health and Safety constraints, building hayricks, autumn harvest suppers, picnics in the harvest field – the memories are endless. Seasons also were more distinguishable, although my children dispute that, putting it down to maternal amnesia!

Will future generations have gentle recollections such as the ones I cherish?

Some of the things that seem to have been lost to modern, intensive farming techniques include the craft of hedge cutting and laying; now rarely seen although it can outlast some fences, confine stock more securely whilst providing habitat for varied wildlife.

And long ago vets and their expensive bills were often not required as the cattle themselves would know what plants to root out as would the farmer also know how to treat them.