The history of agriculture is the story of humankind's development and cultivation of processes for producing food, feed, fiber, fuel, and other goods by the systematic raising of plants and animals.

Historian journalist Deborah Barham Smith gives FarmingUK an exclusive in depth journey into the history of humankind's greatest invention.

Farming first developed around 9000 BC in an area described by archaeologists as the Fertile Crescent, to the east of the Mediterranean Sea and near Mesopotamia; a crescent-shaped strip of land that stretched across the Levant region (now known as Israel, Lebanon, and Syria).

Why did farming begin in the Fertile Crescent? It was an area with a regular rainfall making it perfect for certain grains, emmer 1 and einkhorn 2 and for raising herbivores such as sheep and goats.

In Mesopotamia, soil was more fertile but farming could only develop as irrigation methods developed to supply water to the land.

Nearer home in England, in upland areas such as the Peak District, farming only began around 4000 years ago - whether because of news only gradually filtering through via early trade routes or as a natural evolution from hunter gathering days.

The journey through to current times had several major milestones, as later with the invention of the wheel.

Advent of farming - the Neolithic Revolution

The advent of farming is often called the Neolithic Revolution. The word Neolithic derives from the Greek for new (neo) and relating to stone (lithic); this period is often also known as the New Stone Age.

Innovations in stone-making technology meant that people started polishing stones, rather than just chipping them, as they had done before.

This was significant because, as well as making axes and arrowheads for hunting, they were now able to make tools for farming, such as scythes and hoes.

For these, the stones needed polishing, to give them a flat but sharp edge.

The transition from hunter-gathering to farming is described as a revolution because it constituted the one crucial breakthrough from which all later human advances evolved, transforming every aspect of peoples’ lives.

Types of farming, whether arable or mixed, are determined due to topography and climatic conditions.

With its regular rainfall the Fertile Crescent was ideal for growing grains, and for raising herds of grass-eating animals such as sheep and goats.

Evolution of early farming

It is interesting to note this lengthy timeline for the evolution of early farming:

9000 BC wheat & barley in the Fertile Crescent

8000 BC potatoes in South America

7500 BC Goats & sheep in the Middle East

7000 BC Rye in Europe

6000 BC Chickens in South Asia

The Neolithic Revolution also gave rise to a second kind of economy - the raising of domesticated animals or pastoralism, probably originating in areas unsuited to arable farming.

Hunter-gatherer groups began to supplement their traditional way of life with keeping domesticated sheep, goats, cattle, pigs, horses and so on.

Pastoralists sometimes used fire as a way of turning forest into pasture, and of rejuvenating pasturelands.

This can have a significant impact on the type of plants present in such a landscape; fire and grazing can also prevent forests from growing, and if on mountain slopes, can lead to erosion.

It is very doubtful whether the people involved in this revolution actually noticed that they were living in a time of change since transition took place over many generations.

For hundreds, even thousands of years, early farmers would have continued to forage for fruit and berries and hunt wild game, and only gradually did their economy shift more towards agriculture; to graze a few sheep and cattle and to grow limited crops such as pulses, beans and cereals.

Once domesticated, early farmers bred their animals to improve their usefulness to humans, and soon they were yielding not only meat for food and skin for clothing, but also milk for additional nutrition.

They also produced manure, an excellent fertiliser and fuel.

Textile technologies - superior in every way

Textile technologies were also very important to early farmers. Whereas hunter-gatherers had used the skins of animals for clothing, the domestication of plants and animals gave farmers access to new textiles, superior in every way.

Flax (for making linen) was one of the first recorded crops; and with sheep and goats, people then had regular access to animal wool.

All these fibres required processing to make them fit to wear, with spinning and weaving being the core activities.

Hunter-gatherers knew simple spinning techniques, which only required small sticks around which to wrap fibres.

These gradually evolved into hand-spindles, a process completed by 5000 BC at the earliest.

A form of enclosure in England started as far back as the Royal forests in the Conqueror’s time and before, when the king would require those areas to be maintained solely for his and the nobles’ use in which to hunt.

Around the 13th century granges, (farming estates belonging to the monastery) were set up by abbeys and monasteries, with the monks farming huge flocks of sheep, exporting their valuable fleeces as wool to Europe; this invariably followed the eviction of the peasant farmers who had previously farmed there.

Around 1500 enclosed fields began to appear, able to contain animals and allow more intensive farming methods to be established.

Some of these fields can still be seen and often contain terraces and strip lynchets.

The latter were S shaped banks of earth that built up on the downslope of a field ploughed & furrowed over a long period of time and could conceivably assist in acting as a rainwater reservoir to aid irrigation.

By the 18th century more fields were taken in and enclosed by stone walls and hedges; man has always wished to show his ownership and these served two important purposes: both to define tenure but also to contain stock.

The invention of the plough

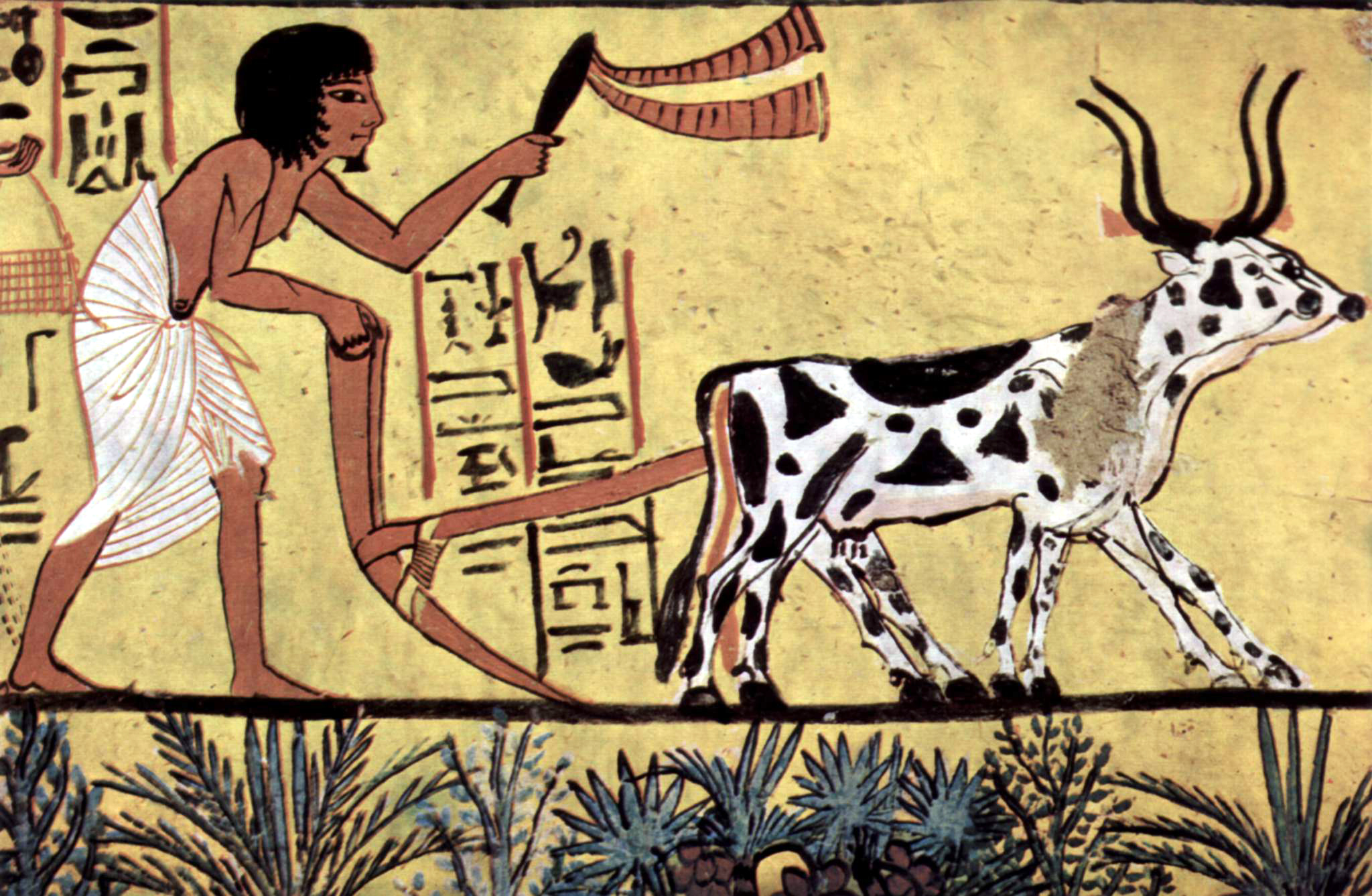

Crucial to the development of early agriculture was the invention of the plough.

Very early farmers had used sticks to dig and hoe trying to prepare the ground for cultivation.

This was far from satisfactory as the land soon became exhausted, so to create new ground fire was used to clear stumps and brush left from tree felling, leaving the soil rich in lime & potash.

The new land would then last through a few good harvests and the process would need to start over again.

This was known as slash and burn shifting farming (or swidden - late 18th century word, variant of dialect verb swithen to burn).

From around 4000 BC, using cattle transformed farming, enabling larger areas to be ploughed so cultivating the soil deeper.

Castrating bulls turning them into oxen seems to have happened in Northern Iraq simultaneously which also assisted ploughing.

A later invention of the yoke in Mesopotamia revolutionised further with the ability to bind two beasts together, so pulling heavier ploughs.

This was the first intensive farming since the deeper the ground was turned the more slowly it became exhausted.

Cattle and other animal manure was also being utilised to help fertilise.

In later centuries when the system of regular crop rotation was introduced, this also helped to replace the nutrients in planting areas.

Irrigation fluctuated in complexity in different areas according to the terrain and amounts of rainfall.

The Lake District is not an area known for water shortages for instance, however in arid areas, man had to be inventive digging wells and channels, and building apparatus (such as the shadoof in Egypt - a pole with a bucket and counterbalance used especially for raising water).

The domestication of the horse

Between 4000 and 3500 BC, groups of people first domesticated horses.

They did so for their meat and milk, rather than for riding. Some however may have been used to drag primitive sledges along the ground, to help carry goods.

Most notably, the wheel had arrived by 4000 BC, and a few hundred years later they were being fixed to ox carts.

One animal that receives very little credit historically but was a key player in the evolution of farming and (according to George Powell, a public speaker and farming aficionado) so deserves far more recognition is the humble ox, which will be explored in part.

By 3500 BC most human beings had become farmers of sorts, remaining so until the 19th or even the 20th century, depending on which part of the world; agricultural methods having been largely spread by the slow migration of the farmers themselves.

It therefore took several millennia for agricultural techniques to spread throughout Western and Southern Asia, across Northern Africa into Europe.

Wherever farming developed, the more reliable food source it produced which led to a massive upswing in population.

But on the downside there were dramatic reductions in the variety of local flora and fauna, as more and more land was given over to fewer varieties of plants and animals.

Humans deliberately altering the land

For the first time, humans were deliberately altering the land for their own purposes.

Farming radically transformed society; hunter gatherers had previously lived in small family groups building temporary shelters and being fairly nomadic, whereas farmers now began to settle creating larger habitations wherever the land was more fertile, such as in river valleys.

Neolithic farming practices had been very unproductive, with early farmers generally able to grow only just enough food for their own needs; meaning that almost everyone had to spend their time in agriculture or related activities.

Only with the spread of iron tools, (less expensive than bronze) in the centuries after 1000 BC, could Neolithic practices at last be developed.

The spread of agriculture would have greatly stimulated trade; the benefit of growing cereal staples such as wheat and barley was that it could be stored for a long time before eating, unlike fruit, berries or meat.

Newly built granaries now enabled humans to survive extremes such as drought and also to trade with their neighbours, encouraging the growth of trade routes over longer distances.

North versus South

In the UK, farming differs between the northern uplands and southern lowlands.

The north is not noted for arable farming, with the terrain lending itself more to rearing beef and dairy cattle, grazing sheep and growing animal feed crops such as hay and silage; although the occasional field of maize, root crops or cereal can be seen as well as the occasional pig or poultry farm.

In the lowlands, areas can sustain larger fields of rich pasture that can support dairy herds as well as beef cattle and sheep.

One of the most notable historic events to influence Britain was the introduction of the General Enclosures Acts of the 1800s which resulted in wall building on a wide scale.

This gave people the right to enclose common land, claiming it for themselves. Since this was invariably done by the nobility, it was a tragedy for the small man, who lost his right to pasture on commons – apart from the bestowing of stints 4.

An anonymous 17th poet coined the lines:

‘The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the Common.

But lets the greater felon loose

Who steals the common from off the goose.’

This really identified the upper classes robbing the Commoners rights by legal trickery.

The advent of mechanisation

However the real revolution in farming, now known as an industry, was the advent of mechanisation, firstly with the steam engine and then the tractor.

In 1892, John Froelich invented and built the first gasoline/petrol-powered tractor in Clayton County, Iowa, USA.

A Van Duzen single-cylinder gasoline engine was mounted on a Robinson engine chassis, which could be controlled and propelled by Froelich's gear box. The tractor transformed what had been more of a village industry up until then.

The agricultural tractor is specifically designed to deliver a high torque (tractive effort) at slow speeds, for the purpose of pulling a trailer or other machinery.

Many farming tasks now became mechanised, originally for tillage – the preparation of soil by mechanical agitation of various types, digging, stirring, and overturning.

Implements could be towed behind, or mounted on the tractor such as a bale lifter.

The enormous machines that are now available can cut down several processes into one sweep of a field such as a combine harvester.

With vast cost prices, and numbers of extras taken as standard such as on-board computers that know where to drive within the field, CB radios, etc it is no wonder that many farmers choose to use contractors for some of the more intensive jobs.

New Holland Agriculture reclaimed the Guinness World Records title, harvesting an impressive 797.656 tonnes of wheat in eight hours with the world’s most powerful 653hp CR10.90 combine. When launched it cost a staggering £566,896.

'Humankind's greatest invention': The History of Agriculture - Part Two will be published tomorrow (6 October).